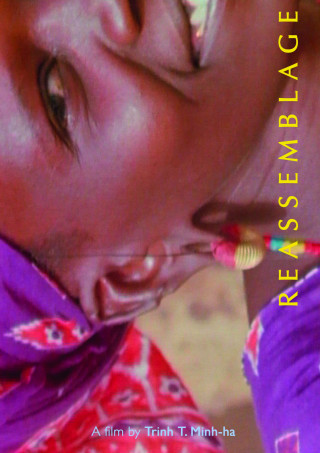

Reassemblage by Trinh Minh-Ha

February 26, 2020

The first element that caught my eye in Trinh Minh-Ha’s film, “Reassemblage,” was that it is filmed in such a way that it imitates the perspective of a person. Whether this was specifically intended or not is unclear yet it is evident, from reading “The Totalizing Quest of Meaning”, that Minh-Ha strove to achieve the truest depiction of life. However, unlike many other filmmakers, her pursuit of validity reevaluated the “truth” upheld in the anthropological field and what makes a “good” documentary.

The entirety of the film has a poetic nature to it—cyclic repetitions, the juxtaposition of beauty with rot and life with destruction (fire). It is captivating and warming yet uncomforting and difficult to decipher at the same time. I think it is in this way that makes Minh-Ha’s reality as close to true reality as possible. There will always be the possibility of a different interpretation; nothing in life desires to be understood. She condemns modern anthropology for putting too much emphasis on meaning; this does not extend to reality. We see the world through glimpses of focus and only find meaning when stimulated by an image that calls us to reflect.

In addition to her juxtapositions, there is another crucial editing technique that Minh-Ha utilizes to replicate or “reconstruct” reality. This is her use of zoomed shots. Artistic shots of a Senegalese woman’s ear, her braids, her nipple, etc.. replicate the actions of focus we make with our eyes. I felt as though Minh-Ha anticipated the impulses of my eyes to dart to a woman’s features to make sense of her whole. In doing this, Minh-Ha also gives a sense of respect and exaltedness. Although “the close-up is condemned for its partiality,” as Minh-Ha recognizes, the filmmaker can put “(the camera’s) intrusion to use and provoke people into uttering the ‘truth’ they would not otherwise unveil under ordinary situations,” (Minh-Ha, 34). We don’t have access to a simple image of her being, as with a wide-angle. We are forced to learn her, hear her “truth,” and have patience in knowing her. In one particular shot (but an angle frequented throughout the film) you see a woman with her baby seen from an upward angle. She fills the frame and with the sun behind her, she is illuminated in importance and pure power. She is an almighty provider, an agent of productivity within her community. A “truth” overlooked by the men in her village.

However, there is conflicting interest when giving your audience unbridled access to these vulnerable images. These women look directly into the camera and the camera serves as an outlet to the screen and to your own eyes which draws you in. Locking eyes directly with these women, you feel that you know them, understand the meaning in their gaze. “Watching her through the lens, I look at her becoming me, becoming mine,” Minh-Ha notes in her film. By recognizing this falsity of subjectiveness that happens even when trying to reframe her role as a subjective filmmaker, Minh-Ha exemplifies self-awareness. This self-awareness brings viewers and herself down from their subjective positions and closer to the grounds of reality. Minh-Ha extrapolates this in the “Totalizing Quest for Meaning.” “A documentary aware of its own artifice is one that remains sensitive to the flow between fact & fiction,” (Minh-Ha, 41). True and existing reality is inimitable but acknowledgement of this enables a more impartial lens capable of capturing the main “truths”.

Another point that I considered while watching these short cuts of these women is the message about gender inequality present in anthropological film. The female nudity in Robert J. Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North,” was objectifying. It adds no dimension or additional purpose to his cinematic focus and contrasts the lack of any vulnerable images of the men. The two wives are seen merely as “happy-go-lucky” bystanders to Nanook’s great journey and courage. In “Reassemblage,” however, the women asked Minh-Ha to film them; they wanted to be perceived. It was an act of defiance and self-confidence. The closeness of the shot of the nipple was so intimate it makes its viewers uncomfortable in their seats. We see a difference between crude and unsolicited nudity and that which showcases empowering motherhood, femininity, and nature. However, this is an element not true to reality. This serves a purpose, though, as a reality through a woman’s eyes is imposed upon its male viewers. It forces them to see these women in ways maybe they don’t pay attention to in their realities. They see her breasts and body, not as beautiful parts to her whole but a whole for feasting eyes. This reality, therefore, exposes truths about these women and Minh Ha captured it.

“Nanook of the North” is an example of when this pursuit of “truth” goes wrong. Flaherty sought to compose a truth of his own. He wanted to materialize a popular stereotype of Inuit people in order to preserve a favorable “fleeting” image of them before the influences of outer civilization but in turn, just falsified their culture. Fatimah Tobing Rony claims Nanook is a “product of a hunt for images,” (Rony, 100). Flaherty filmed only what would fit his own schemas and vision of what he wanted his audience to take away from his film. For example, it was held that the Inuit were primitive people ignorant of guns but they did use them for hunting at the time of filming. Flaherty knew that this would dispel the image of the “cuddly primitive (Inuit) man” and urged them to not use guns on filmed hunts even when their lives were put in danger, (Rony, 99). These methods construed and twisted the truth to achieve a “good” documentary; one where the “subject matter is ‘correct’ and (one) whose point of view the viewer agrees with. What is involved may be a question of honesty but it is often also a question of (ideological) adherence, hence of legitimization,” (Minh-Ha, 36). There is a certain self fulfilling prophecy commonly seen where a filmmaker produces a film adhering to previous bias and expectation. The focus is misplaced on that which is appealing and not on what is true.

“Nanook of the North” helped create an illusionist basis of the documentary but films like “Reassemblage” and Luis Bunel’s “Land Without Bread” destroyed this, (Ruoff, 53). Both works are blatantly self-aware and function to condemn the “classic” mode of ethnography at the time. “Reassemblage” achieves this goal through poetry and strategic cinematic elements that portray a “truer” sense of reality than was recognized by fellow anthropologists. On the other hand, “Land Without Bread” amplified the illusions that were fabricated by for example Flaherty in order to reveal the issues within documentary processes and the misplaced role of the filmmaker. Like in “Nanook of the North,” Bunel uses an authoritarian voice-over, imposing his interpretations on everything that enters the frame, and an intertitle reading, “Las Hurdes is a sterile and inhospitable area where man is obliged to fight, hour by hour, for his subsistence.” This parallels Flaherty’s intertitle in “Nanook of the North” introducing “the ‘barren lands’ and ‘sterile environment’ of Northern Canada,” (Ruoff, 49). Bunel attempted to reveal the haughty position of filmmakers when they characterize these external peoples and not give them the chance of portraying their own realities. A previously designed reality was already in the making and the filming process had become a process of fitting this mold. By making fun of these ridiculous assumptions and methods with satirical means, Bunel comes out with a radically self-aware film that steals the acclaim of these upheld “classic” documentaries. Additionally, to do this, Bunel uses a technique also utilized by Minh-Ha: juxtaposition. Many critics assumed Bunel’s use of light-hearted and uplifting orchestral pieces paired with scenes of the suffering and the hunger of the Las Hurdes people was in bad taste but it, in fact, served as a cinematic tactic. This juxtaposition, like that of Minh-Ha, exposes the disillusioned attitude of “foreign” peoples as “happy-go-lucky” subjects to be perceived and whose opinions and desires aren’t legitimate. They are poor and pitiful and aren’t given a voice. Minh-Ha gives the Senegalese women identity and voice and allows them to reclaim a principal and active role in the documentary. Both films cast-off illusion by centering on the reality of people behind the blur of a “classic” ethnographic lens.

“Reassemblage” is a near-perfect response to classic ethnographies of that time in presenting all that is lacking and misconstrued in their field. Minh-Ha replaces the focus and “meaning” of film through self-awareness of imposer implications and impartialness in being. She reevaluates what a filmmaker should strive for, and in a direction away from creating a “good documentary.” Her lens breaks down expectations and illusion for “true” capture; a reality free from artistic constraints and expertise platforms.

Fire of Love by Sara Dosa

September 2nd, 2022

Some of the most stunning shots I’ve ever bore witness too. They truly capture that feeling of being dwarfed by nature and the way this trivializes all other human endeavors in the social/capitalist sphere. How these two worlds (natural and social) are able to exist beside each other and feel like different planets sometimes makes me think that humans have purposely cut themselves off from acknowledging the power of nature; this denial allows for guiltless capitalism and delusions of human power. Being away from nature for so long and then reconfronting it (at least for me) makes me forget my body and image constantly mirrored back to me by society. I wonder if Katia and Maurice never fully identified with their social selves and that’s why going back to the social world made them feel like aliens. I definitely think humans need to amend and build up their relationship with nature.

October Country by Michael Palmieri and Donal Mosher

December 19, 2022